So our son the litigation lawyer made the lead story in yesterday's Globe and Mail. OK, he turns up near the end of the convoluted yarn. But I had no idea that back in 2005, when he was a law student, Carlin was involved in such cloak-and-dagger skulduggery. He has been practicing now for more than a decade with Duvernet, Stewart, an amazingly successful boutique firm based in Mississauga.

But here is Globe reporter Mark MacKinnon, writing of 2005 and looking for Boris Birshtein: "After trying, and failing, to deliver the documents at two Toronto addresses, the law student, Carlin McGoogan, made the 75-minute drive north to Shanty Bay, a quilt of elegant farm and cottage properties on the western shore of Lake Simcoe. Faced with a gated driveway and what he described as a 10-foot-high fence at Mr. Birshtein’s home there, Mr. McGoogan taped Alon Birshtein’s statement of claim to the iron gate. This fall, 13 years later, I found myself following in the student’s footsteps. . . .

Like Mr. McGoogan before me, I found myself with only the Shanty Bay address left to try. So I rented a Chevrolet that I hoped looked nondescript, and headed north from Toronto on an early autumn afternoon. I found the property exactly as Mr. McGoogan had described it – but on this day, the gate was open, though dense forest obscured any view of what lay beyond. . . ."

Today, answering my email queries from a ski hill in the Eastern Townships, Carlin revealed that on another occasion, he did get into the mansion at Shanty Bay . . . and even spent time in the steam room. All this was news to me. Speaking as a father, I can say only that at such revelations, the mind reels. But click here for the MacKinnon yarn.

adventure canada

Dead Reckoning

George Orwell

Margaret Atwood

scotland

The Devil made me jive with Margaret Atwood

December 19, 2018

The Devil made me do it. I knew it was wrong. I knew I had no business inviting an iconic Canadian writer out onto the dance floor. I knew people would hate me for it. Who did I think I was? But a little voice told me to go ahead and ask her to dance. Graeme was there, standing tall. Sheena was there, camera in hand.

But I'd better come clean. We had danced together at least once before, Ms. Atwood and I, at a meeting of the The Writers' Union of Canada. This was back in the day. 1985, I think it was. Things were different then.

Now it was 2011 and I had reason to be wary. We were voyaging around Scotland with Adventure Canada, having a blast, and had ended up in this community hall on the island of Jura. George Orwell had lived somewhere in this vicinity. Here on Jura, he had discerned that Big Brother was always watching. Coincidence? I thought not.

But I shrugged off all that and plunged ahead. I mention this in what you now learn is my "year-ender" because I grow skeptical about the way browsers function. My stats tell me that my all-time most popular blog post, with 17,300 viewings, is entitled A younger male writer crosses swords with Margaret Atwood. I ask you: have more than 17,000 people cast their eyes over my divigations? Or does that total derive from an algorithm that automatically counts "one" every time it chances upon "Margaret Atwood." So, yes, this is a test. That, anyway, is my story.

My other greatest hits are also all included in last year's greatest hits, which featured voyaging in the Northwest Passage, my book Dead Reckoning, and Let's Invite Scotland to Join Canada. I remind myself that this means not that I have been less entertaining this year than last, but that "all-time" is cumulative, and so it takes more than one year to reach the upper echelons of even these modest heights.

But now I refrain from adding a second photo to this post. The Devil insists that I could justify an image of the cover of Dead Reckoning. No, I say, and stand firm. People would accuse me of being shameless and worse and that . . . that would hurt my feelings. For the rest, I would add: Merry Christmas! Happy New Year. Party on!

But I'd better come clean. We had danced together at least once before, Ms. Atwood and I, at a meeting of the The Writers' Union of Canada. This was back in the day. 1985, I think it was. Things were different then.

Now it was 2011 and I had reason to be wary. We were voyaging around Scotland with Adventure Canada, having a blast, and had ended up in this community hall on the island of Jura. George Orwell had lived somewhere in this vicinity. Here on Jura, he had discerned that Big Brother was always watching. Coincidence? I thought not.

But I shrugged off all that and plunged ahead. I mention this in what you now learn is my "year-ender" because I grow skeptical about the way browsers function. My stats tell me that my all-time most popular blog post, with 17,300 viewings, is entitled A younger male writer crosses swords with Margaret Atwood. I ask you: have more than 17,000 people cast their eyes over my divigations? Or does that total derive from an algorithm that automatically counts "one" every time it chances upon "Margaret Atwood." So, yes, this is a test. That, anyway, is my story.

My other greatest hits are also all included in last year's greatest hits, which featured voyaging in the Northwest Passage, my book Dead Reckoning, and Let's Invite Scotland to Join Canada. I remind myself that this means not that I have been less entertaining this year than last, but that "all-time" is cumulative, and so it takes more than one year to reach the upper echelons of even these modest heights.

But now I refrain from adding a second photo to this post. The Devil insists that I could justify an image of the cover of Dead Reckoning. No, I say, and stand firm. People would accuse me of being shameless and worse and that . . . that would hurt my feelings. For the rest, I would add: Merry Christmas! Happy New Year. Party on!

Flight of the Highlanders

Highland Clearances

Sheena Fraser McGoogan

Researching the Highlands inspires magical paintings

December 17, 2018

Faithful readers will know that I have been researching a book about the Highland Clearances. It is called Flight of the Highlanders: Canada's First Refugees. And it will be published next autumn by Patrick Crean Editions / HarperCollins Canada. But this post is not about that.

This is a post about Sheena Fraser McGoogan, with whom I have spent the past few years traipsing around the Highlands. While I scribble notes, she sketches and takes photographs.

Then, when she gets home, she heads out into her back-yard studio, where she mixes and matches and magically transforms her gleanings into colorful acrylic paintings.

Then, when she gets home, she heads out into her back-yard studio, where she mixes and matches and magically transforms her gleanings into colorful acrylic paintings.

Usually, Sheena paints large if not massive. But in the past few months, she has turned her hand to producing a few small gems -- twelve inches square. Here we see three of them. I have been authorized to offer these up as possible Christmas presents at a sale price . . . wait for it . . . of $350 each. If you covet one, or OK, three for $900, contact sheena.mcgoogan@gmail.com.

This is a post about Sheena Fraser McGoogan, with whom I have spent the past few years traipsing around the Highlands. While I scribble notes, she sketches and takes photographs.

Then, when she gets home, she heads out into her back-yard studio, where she mixes and matches and magically transforms her gleanings into colorful acrylic paintings.

Then, when she gets home, she heads out into her back-yard studio, where she mixes and matches and magically transforms her gleanings into colorful acrylic paintings. Usually, Sheena paints large if not massive. But in the past few months, she has turned her hand to producing a few small gems -- twelve inches square. Here we see three of them. I have been authorized to offer these up as possible Christmas presents at a sale price . . . wait for it . . . of $350 each. If you covet one, or OK, three for $900, contact sheena.mcgoogan@gmail.com.

adventure canada

Broch of Gurness

Clestrain

Kirkwall

Orkney

Stromness

Stone village in Orkney proves one of a kind

December 09, 2018

A massive storm swept through this region and

so we remained tied up in Kirkwall. In retrospect, this looked providential. We

were able to visit the Broch of Gurness and the town of Stromness, and those of

us who had not yet managed to explore Kirkwall got to visit St. Magnus

Cathedral, with its John Rae memorial and gravesite, and the dazzling Orkney

Museum. At least eight people sallied forth to check out two distilleries -- Highland Park and Scapa. They returned

expressing satisfaction.

Local guides joined Adventure Canada staff aboard the buses

and added colour and context. We got out to the Broch of Gurness, arguably Orkney’s most

under-rated archaeological site. Here an Iron Age dwelling tower stands at the

centre of a well-preserved stone village, offering a unique experience that

extends into the Viking era. Visitors can get right down into the site and poke

around in the ruins of ancient people’s houses.

This is vastly different from walking around outside

even the wonderful Skara Brae, where you are forced to become the 21st

century observer. At Gurness, you scramble over inconvenient slabs of rock and

march up a winding causeway to duck and plunge through an awkward low doorway.

More than one visitor predicted that ours will be the last generation to enjoy

Gurness with such freedom.

We drove also to Stromness, home to 2,500

inhabitants (Kirkwall, the capital, claims 8,500). Everyone loves the atmosphere

of this town, the main street winding along the coast, the sporadic views of

the water, the cobble stones in the streets. Three times a day the NorthLink

Ferry glides into the harbour from mainland Scotland to deliver and collect

cars and people.

Riding in buses, we visitors enjoyed the open,

panoramic views of the big sky, the rolling hills, the

expanses of water. In Kirkwall, St. Magnus is famous for obvious reasons. But

the Orkney Museum across the main street . . . that’s a happy surprise. Here we

encountered the Picts, the Celts, the Vikings, the Lairds. So much history, so

little time.

John Rae

Kirkwall

Neoliithic adventure Stonehenge

St. Magnus

Stromness

Yo, Orkney! Skara Brae to Clestrain

December 08, 2018

People were living at Skara Brae before

Egyptians built the pyramids. By the time other neolitithic folk started work

on Stonehenge in England, they had resided here, facing out over the salt

water, for three to four hundred years – and even had time to abandon the site.

To stand here today, in the 21st century, gazing out at surf-worthy

waves, proved both humbling and awe-inspiring. More than one person

incidentally gave thanks that our expedition leader had decided we would

overnight at the dock in Kirkwall, rather than plunge out into what would certainly

have been one horrendous night on the water.

But what a place is Skara Brae – the

best-preserved Neolithic village in northern Europe, and a site that offers an

entree into the daily lives of people who lived 4,500 years ago. Here they

cooked, there they ate, and here, just here, they curled up and slept. Today,

as well, while rambling around with Adventure Canada, we visited the nearby Ring of Brodgar, a world-famous circle of

standing stones, and passed by a recently begun archaeological dig between the

two, the Ness of Brodgar, that points back even earlier, to the Mesolithic era

of 7000 years ago, when hunter-gatherers roamed these hills.

Roll on to the Hall of Clestrain, which

overlooks Hoy Sound near Stromness. Birthplace in 1813 of Arctic explorer John

Rae, this listed building is now the focus of a restoration campaign led by the

John Rae Society, which is determined to turn Clestrain into a world-heritage

centre. Three buses shuttled passengers from one location to another, while

other visitors rambled around Kirkwall, visiting St. Magnus Cathedral, which

contains a gorgeous memorial to Rae, and also the explorer’s grave, situated

behind this magnificent 12th century edifice.

Rumor had it that some travelers indulged in serious

retail therapy, and suggestive evidence turned up in certain newly observed

artifacts. Come evening, two Orcadians came aboard. Andrew Appleby, president

of the John Rae Society and a professional potter from nearby Harray (the

Harray Potter), invited people to visit his studio, where he throws pots. And

native Orcadian historian Tom Muir, president of the Orkney Story-Teller’s

Association, entertained with a series of entrancing tales that ranged from the

dark and foreboding to the sublime and sorrowful. His was a tour de force performance.

adventure canada

Blackhouse Village

Callanish Standing Stones

Isle of Lewis

Outlander

Outlander lives on the Isle of Lewis

December 07, 2018

We arrived on the Isle of Lewis around 6 a.m., precisely on

schedule, and tied up at the dock so that passengers could walk off the ship.

That we did with voyagers organized into six groups. We piled into three buses

in the morning, the same three in the afternoon, and everyone got a chance to

ride the island in a circle with no stress, no bother. Clockwork.

This was our Adventure Canada voyage around Scotland last June.

On our bus we had a wonderful guide named Doro,

short for Dorothea, who had an answer for every question, no matter how arcane.

The Dun Carlaway Broch dates from around the final century B.C., making it one

of the last to be built. It remained in use, probably as both castle and vertical

farmhouse, until the Vikings arrived in the early 800s. My favorite story

about the broch derives from the 16th century, when the Morrisons of

Ness took refuge here after getting caught raiding cattle from the local MacAulays.

The Morrisons blocked the broch entrance, which was designed for that purpose,

but Donald Cam MacAulay scrambled up the outer wall, threw down burning heather,

and forced the would-be thieves to stumble out to meet their fate.

The Callanish Stones are the largest assemblage

of such mystery objects in all Europe. Dating back 5200 years, they are not

only older than those at Stonehenge but are arranged in the shape of a Celtic

Cross and are also readily accessible. No cars roar past on nearby highways.

And if you have no fear of being shunted off backwards in time, Outlander-style,

you can reach out surreptitiously and touch them.

Even so, on Lewis, I got the biggest kick out of visiting the nine houses at the Gearrannan Blackhouse

Village, which hark back to the 17th century. Here we see how the vast

majority of Highlanders lived for centuries. The village highlight is the

working blackhouse, which has been reconstructed to the year 1955, when

inhabitants adapted and incorporated many of the features of the more modern

“white houses” that arose after the end of the Second World War. A local guide

named Mary, who was born and raised in this village, provided an evocative

depiction of life during this period of transformation.

Before leaving Lewis, passengers got to visit Stornoway.

Home to more than 7,000 people, it is by far the largest settlement in the Hebrides,

and offers a range of shops, services and amenities. Many passengers visited Lews

Castle and enjoyed its wooded walks and museum experience, which included

multi-media atmospherics and a collection of several of the original Lewis

Chessman. A bookstore on Cromwell Street enjoyed a run on Lewis-related books

by mystery writer Peter May . . . and on facsimile chessmen.

adventure canada

Finlaggan

Iona

Oban

Scotland Slowly

Voyage around Scotland proves magical

December 06, 2018

On Day One, we sailed out of Oban not long after 7 p.m.,

with the waters calm and the sun setting among the islands. The arrival and

boarding had brought the usual challenges.But more than half (116) of the passengers had

sailed previously with Adventure Canada and that made the process of boarding easier than

it might have been. Once on board, we made our way to the Nautilus

Lounge, where we proceeded efficiently through the zodiac briefing. Then came the

mandatory lifeboat drill and staff introductions. Expedition leader Matthew

James (M.J.) Swan elaborated on the next day’s doings – a visit to Islay – and

then we headed for our first white-linen-tablecloth dinner.

The story emerged at the small visitors’ centre

and in a series of plaques at the site. It begins in 1153, when in a major sea

battle off the coast of Islay – just a few miles north of Finlaggan – Somerled

defeated Godred IV and forced him to retreat to Norway. A decade later, in

1164, Somerled led an ambitious invasion of mainland Scotland. This was a

crucial moment, the first great clash between two Celtic-World cultures –

Norse-Gaelic and Anglo-Norman.

But soon after landing near Glasgow with tens

of thousands of warriors, Somerled was slain – probably by the lucky throw of a

spear. His massive army, whose troops included a large contingent from Dublin,

withdrew in disarray. Finlaggan became home to the Lords of the Isles –

descendants of Somerled, led by the MacDonalds -- who ruled the western Scottish

Isles until 1494, when mainlanders under King James IV put paid to their

independence.

From Finlaggan, we voyagers traveled by bus and

van to Islay House Square. Now a five-star hotel, Islay House was formerly home

to a Campbell laird. Out front, what was once a thriving courtyard is now a scattering

of shops – and visitors took full advantage. Back on the ship, we enjoyed a

whisky tasting before adjourning to the dining room for the captain’s dinner.

Day three found us visiting Iona Abbey, where that scholarly warrior Saint Columba arrived from Ireland, built a monastery, and established Christianity

in Scotland. The monastery became arguably the most glorious edifice in the

country – though the people of Orkney champion St. Magnus Cathedral. Iona became the burial

site for many Scottish princes and kings.

Day three found us visiting Iona Abbey, where that scholarly warrior Saint Columba arrived from Ireland, built a monastery, and established Christianity

in Scotland. The monastery became arguably the most glorious edifice in the

country – though the people of Orkney champion St. Magnus Cathedral. Iona became the burial

site for many Scottish princes and kings.

A storm had rolled in during the morning as if

to challenge our visit. Gusting winds and light rain had impeded our morning

zodiac cruise to the island of Staffa. Some passengers had hoped to get inside

Fingal’s Cave, famously the locale that inspired a celebrated composition (The Hebrides) by Felix Mendelssohn, as

well as subsequent visits by well-known figures and even an on-location

orchestral performance. The wind prevented entry, as it so often does, but the

cruise proved invigorating and the island itself, created through three

distinct volcanic eruptions, is geologically unique and spectacular. Incredible to think, as geologist David Edwards

later relayed, that in 1772, a farming family was eking out a living on the

rocky island. A few winters appear to have brought them to their senses, and

they were gone by 1800.

Rumour has it that in June 2019, Adventure Canada will again circumnavigate Scotland. http://www.adventurecanada.com/trip/scotland-slowly-june-21-july-1-2019/

(Photos by Sheena Fraser McGoogan . . . except the one in which she appears)

Arctic Return Expedition

Franklin expedition

John Rae

northwest passage

Arctic adventurers recreate trek to Rae Strait

November 27, 2018

The

Arctic Return Expedition is all systems go. A reconfigured four-man team will

set out March 25, 2019 to recreate the most successful Arctic overland expedition

of the 19th century. On his 1854 surveying adventure, accompanied by

an Inuk and an Ojibway, Orcadian explorer John Rae discovered both the terrible

fate of the lost Franklin expedition and the final link in the first navigable

Northwest Passage.

The

Arctic Return Expedition is all systems go. A reconfigured four-man team will

set out March 25, 2019 to recreate the most successful Arctic overland expedition

of the 19th century. On his 1854 surveying adventure, accompanied by

an Inuk and an Ojibway, Orcadian explorer John Rae discovered both the terrible

fate of the lost Franklin expedition and the final link in the first navigable

Northwest Passage.

Next

March, veteran polar adventurer David Reid will lead an outstanding team in

traveling 650 km overland from Naujaat (Repulse Bay) to Rae Strait, following

in the footsteps of John Rae, William Ouligbuck Jr., and Thomas Mistegan. When

personal considerations forced withdrawals, Reid rounded out his team with experienced,

highly skilled adventurers.

The party now includes:

n Canadian adventurer Frank Wolf,

named one of Canada’s top 100 explorers by Canadian Geographic Magazine in

2015. Wolf, the first to canoe across Canada in a single season, also cycled 2,000

km in winter on the Yukon River from Dawson to Nome. He has documented his

adventurers in articles and films and recently published his first book, Lines on a Map (Rocky Mountain Books).

n Scottish adventurer

Richard Smith, PhD, who studied as an astrophysicist, moved into Information

Technology, and served with the Royal Marine Commandos and the Special Boat

Service. Smith has climbed, trekked or kayaked in Alaska, Greenland, Nepal and

the French Alps, and explored the jungles of Belize and the deserts of Oman.

n Adventure

film-maker Garry Tutte, who created an educational web-series from

Mt. Everest, documented a 7000 km car rally from England to Gambia across the

Sahara Desert, and travelled from the remote islands of the Philippines to Hong

Kong to create an award-winning film. In 2017, Tutte led the media team aboard

the Canada C3 expedition as it circumnavigated the country’s 23,000 km

coastline from Toronto to Victoria via the Northwest Passage.

n Reid himself,

who lived on Baffin Island for 20 years and has led, organized

or participated in more than 300 Arctic and Antarctic expeditions, trips and

projects. In that time he has

traveled thousands of miles by dog sled, ski, snowmobile, boat, kayak,

ship, foot and most recently by bike, becoming the first person to cross Baffin

Island by fat-tire bike.

The expedition is hoping to raise funds for the restoration of John Rae's birthplace, the Hall of Clestrain. The flagship sponsor is The Royal

Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS). The award-winning travel company Adventure Canada and Canada Goose are also lending major support. For more details check out the expedition website.

The expedition is hoping to raise funds for the restoration of John Rae's birthplace, the Hall of Clestrain. The flagship sponsor is The Royal

Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS). The award-winning travel company Adventure Canada and Canada Goose are also lending major support. For more details check out the expedition website.

#MeToo

Colette

Ghost Brush

Glenn Close

Katherine Govier

Lady Franklin's Revenge

The Wife

Surely #MeToo should be all over The Wife, The Ghost Brush, Colette, and Lady Franklin?

November 11, 2018

So we caught the hit film The Wife last night. The movie, based on a novel by Meg Wolitzer, features a tour-de-force performance by Glenn Close. But what struck me is that you can change the culture, the time period, the mode of expression . . . yet the story remains the same.

So we caught the hit film The Wife last night. The movie, based on a novel by Meg Wolitzer, features a tour-de-force performance by Glenn Close. But what struck me is that you can change the culture, the time period, the mode of expression . . . yet the story remains the same.

-- In The Wife, Joan Castleman does the writing . . . but her husband Joe wins the Nobel Prize. Backstory set in 1990s U.S.A.

-- The Ghost Brush, by Katherine Govier, is set in Japan in the late Edo period. The daughter Katsushika Oei does the printmaking, her father Hokusai takes the credit.

-- Colette, set in late 19th century France, finds the eponymous heroine doing the writing . . . and her husband Willy reaping the celebrity.

-- Colette, set in late 19th century France, finds the eponymous heroine doing the writing . . . and her husband Willy reaping the celebrity. -- In Lady Franklin's Revenge, which unrolls through Victorian England, Jane Franklin emerges as the real explorer, the one who orchestrates the mid-to-late career of Sir John Franklin . . . yet he is the one celebrated in myth and legend.

-- In Lady Franklin's Revenge, which unrolls through Victorian England, Jane Franklin emerges as the real explorer, the one who orchestrates the mid-to-late career of Sir John Franklin . . . yet he is the one celebrated in myth and legend.

The Wife, The Ghost Brush, Colette, Lady Franklin's Revenge . . . surely #MeToo should be all over this?

People tell me I am too modest and self-effacing. They say, Ken, enough with the shy-and-retiring. You have to stop shunning the spotlight. Lately, in response, I've been banging the drum for the newly released paperback edition of Dead Reckoning. While working up a nifty little song-and-dance, I chanced upon the above slide and The Frozen Dreams Quintet. So of course I thought of Yeats and his rough beast slouching towards Bethlehem to be born. And I realized that, with Christmas whirling toward us, probably I should ask my publisher to drop everything and bring out my Arctic books as a boxed set. Makes sense, right?

adventure canada

Celtic Life International

Scottish Highlands

St. Kilda

St. Kilda evokes Flight of the Highlanders

November 01, 2018

The December issue of Celtic Life International features a gorgeous 3-page spread on a visit to the Scottish island of St. Kilda. We turned up in the vicinity while sailing with Adventure Canada earlier this year. A version of the article, which begins as below, will appear in a 2019 book to be published by Patrick Crean / HarperCollins Canada. We're calling it FLIGHT OF THE HIGHLANDERS: Canada's First Refugees.

Unbelievable.

Overwhelming. Voyagers who have visited the archipelago of St. Kilda more than

a dozen times declared this The Best Visit Ever. If they had said anything

else, the rest of us would not have believed them. Bright sunshine, balmy

temperatures, no wind . . . was there a cloud in the sky?

During the

morning, when we arrived in this vicinity aboard the Ocean Endeavour, the day

had looked less promising. Most ships that reach St. Kilda never land a soul.

Winds too rough. Today, a serious swell caused people to doubt we would make it

ashore. But in an inspired bit of decision-making, our Adventure Canada

expedition leader turned the day upside down, switching early with late.

Instead of

attempting a morning landing, we sailed directly to the bird cliffs of Stac

Lee, home to the largest colony of gannets in the world. As the winds died and

the sun came out, the captain showcased his navigational skills. Seventy or

eighty metres in front of the towering black wall, he held ship steady. We

found ourselves gazing almost straight up at a whirlwind of wheeling birds more

than 400 metres above. I’m no birder but this was impressive.

A back-deck

barbecue kept us busy as we sailed to Hirta, the archipelago’s main island.

We’re talking about the remotest part of the British Isles, 66 kilometres west

of Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides. I had landed here once and knew enough to

remain dubious. But on arriving, we found the swell had receded. We piled into

zodiacs and zoomed ashore. Incredible!

St. Kilda is

one of very few places with Dual World Heritage Status for both natural and

cultural significance. Bronze Age travellers appear to have visited 4000 to

5000 years ago, and Vikings landed here in the 800s. Written history reveals

that a scattering of people (around 180 in 1700) rented land here from the

Macleods of Dunvegan on the Isle of Skye. While living in a settlement (Village

Bay) of stone-built, dome-shaped houses with thatched roofs, they developed a

unique way of life, subsisting mostly on seabirds.

Gradually, as

better ships enabled more contact with the outside world, they came to rely

more on importing food, fuel and building materials. They constructed better

houses. In 1852, 36 people emigrated to Australia, so beginning a long slow

population decline. During the First World War, a naval detachment brought

regular deliveries of food. When those ended after 1918, St. Kildans felt

increasingly isolated. In 1930, the last 36 islanders were evacuated to the

Scottish mainland.

During our June

visit, we strolled along the curved Village Street where these last holdouts

had resided. Most passengers found time to climb the saddle between two high

hills. After a rise in elevation of perhaps 150 metres, we came to a cliff

edge. Gazing back over the vista in the sun – the Village Street, the scattered

beehive cleits, the Ocean Endeavour in the harbour, the occasional zodiac, the

distant mountains – a consensus emerged: unbelievable!

Beyond this,

everyone had their personal highlights. I registered two. The first came when I

found the beehive cleit that stands today on the foundations of what was once

the home of Lady Grange. She was an articulate, headstrong woman who, in the 1730s, spent eight

lonely years as a prisoner on this island. While living in high-society

Edinburgh, she learned that her husband was having an affair in London.

Infuriated, she had threatened to expose him as a treasonous Jacobite.

That gentleman – who was indeed conspiring with

such powerful figures as Macdonald of Sleat, Fraser of Lovat, and Macleod of

Dunvegan -- responded by having his irrepressible wife violently kidnapped and

bundled off, ultimately, to this almost inaccessible island. Here Lady Grange endured

as the only educated, English-speaking mainlander on Hirta except for the

minister and his wife. Her house is long gone, but a ranger directed me to the

hut that stands today on its foundations. Made me shiver.

That gentleman – who was indeed conspiring with

such powerful figures as Macdonald of Sleat, Fraser of Lovat, and Macleod of

Dunvegan -- responded by having his irrepressible wife violently kidnapped and

bundled off, ultimately, to this almost inaccessible island. Here Lady Grange endured

as the only educated, English-speaking mainlander on Hirta except for the

minister and his wife. Her house is long gone, but a ranger directed me to the

hut that stands today on its foundations. Made me shiver.

(To read the rest of the article, check out the December issue of Celtic Life International.)

Arctic exploration

Dead Reckoning

Erebus

Michael Palin

Northhwest Passage

Michael Palin's Erebus and Dead Reckoning look alike because they belong together

October 24, 2018

"What the publishing industry hath joined

together let no bookseller put asunder." That's the way I see it.

Faithful readers have been nudging me: "Have

you seen the cover of Erebus? Michael

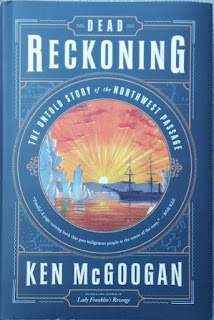

Palin's new book? Doesn't it remind you of the cover of Dead Reckoning: The Untold Story of the Northwest Passage?"

Well, now that you mention it, I say, yes, yes it does. It’s a

perfect match. And that is as it should be. The two books complement each other.

Ideally, they form part of the same whole. Erebus

tells the story of a single ship. Dead

Reckoning puts that story in context. The two books should be displayed, bought,

sold and read together.

When I was asked to provide a blurb for Palin’s

book, I wrote: “At this late date, and against all odds, Michael Palin has

found an original way to enter and explore the Royal Navy narrative of polar

exploration. Palin is a superb stylist, low-key and conversational, who

skillfully incorporates personal experience.”

Dead Reckoning, published in

hardcover last autumn, drew an equally enthusiastic response. The paperback

edition, which is now rolling into bookstores, quotes a couple of reviews on

the back cover. “This book is a masterpiece, setting the standard for future

works on Arctic exploration,” one reviewer wrote. “Dead Reckoning could be the best work of Canadian history this

year.”

Dead Reckoning, published in

hardcover last autumn, drew an equally enthusiastic response. The paperback

edition, which is now rolling into bookstores, quotes a couple of reviews on

the back cover. “This book is a masterpiece, setting the standard for future

works on Arctic exploration,” one reviewer wrote. “Dead Reckoning could be the best work of Canadian history this

year.”

A second wrote: “Outstanding. . . . This is

not the Canadian history that we learned in school.” And a third: “A sweeping

work that sets out to bring the Indigenous contributors to northern exploration

into the story as participants with names – not just tribal affiliations or occupations

stated as ‘hunter’ or ‘my faithful interpreter.”

You get the idea. Since Palin’s book is

published by Random House Canada and my own by HarperCollins Canada, I don’t

think we can expect to see a boxed set any time soon. No worries. My advice

would be that, when you buy the one, you should always pick up the other. Hey, just my opinion.

Creative nonfiction

Louisbourg or Bust

MFA program

Ryan Shaw

University of King's College

Beautiful quest narrative finds Dude Quixote hauling a surfboard along Atlantic Coast

October 20, 2018

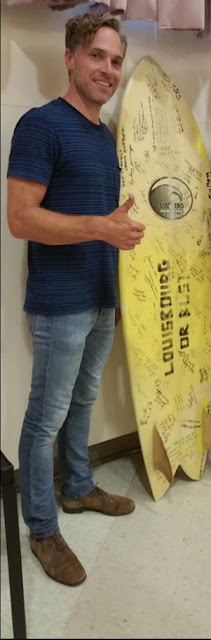

Say hello to my friend Ryan (R.C.) Shaw. And his surfboard, Old Yeller. Ryan is launching his first book tonight in Toronto. It's called Louisbourg or Bust. And it's one of 19 books (and counting) produced by graduates of that unique MFA program in Creative Nonfiction offered at University of King's College in Halifax.

That's the one in which, full disclosure, I serve as a mentor. When Ryan asked me for a book-jacket squib, I was delighted to offer a few words: "This crazy beautiful quest narrative puts Don Quixote on a bicycle and sends him out to face history with a surfboard. Half hilarious dream-adventure, half marathon-nightmare, Louisbourg or Bust is all madcap love letter to Nova Scotia."

The launch is happening at 865 Bloor Street West from 7 p.m., and if you're looking for a bunch of folks who are ready to party, I'd suggest that this is where to find them.

In related news, things will be more sedate -- but equally welcoming -- on November 12 at the Toronto Meet and Greet for interested potential students. What happens is that the program's faculty, mentors, students, and alumni get together for wine and nibblies in the boardroom of Penguin Random House Canada. That's at 320 Front Street West, Suite 1400.

From 6 p.m. onward, you can hang out with us while contemplating whether this program might work for you. We're talking two years during which you combine short intense residencies in Halifax, Toronto and New York with ongoing one-on-one mentoring with professional nonfiction writers. At the end, you graduate with a degree, a polished book proposal, and a substantial portion of a finished manuscript -- or maybe, if you're like Ryan, a contract to publish a book. Anyway, lots more here:

https://ukings.ca/area-of-study/master-of-fine-arts-in-creative-nonfiction. And maybe see you tonight or on Nov. 12.

That's the one in which, full disclosure, I serve as a mentor. When Ryan asked me for a book-jacket squib, I was delighted to offer a few words: "This crazy beautiful quest narrative puts Don Quixote on a bicycle and sends him out to face history with a surfboard. Half hilarious dream-adventure, half marathon-nightmare, Louisbourg or Bust is all madcap love letter to Nova Scotia."

The launch is happening at 865 Bloor Street West from 7 p.m., and if you're looking for a bunch of folks who are ready to party, I'd suggest that this is where to find them.

In related news, things will be more sedate -- but equally welcoming -- on November 12 at the Toronto Meet and Greet for interested potential students. What happens is that the program's faculty, mentors, students, and alumni get together for wine and nibblies in the boardroom of Penguin Random House Canada. That's at 320 Front Street West, Suite 1400.

From 6 p.m. onward, you can hang out with us while contemplating whether this program might work for you. We're talking two years during which you combine short intense residencies in Halifax, Toronto and New York with ongoing one-on-one mentoring with professional nonfiction writers. At the end, you graduate with a degree, a polished book proposal, and a substantial portion of a finished manuscript -- or maybe, if you're like Ryan, a contract to publish a book. Anyway, lots more here:

https://ukings.ca/area-of-study/master-of-fine-arts-in-creative-nonfiction. And maybe see you tonight or on Nov. 12.

Arctic exploration

Arts and Letters Club

Canadian Federation of University Women

Carlton Theatre Lecture Series

Dead Reckoning

Frozen Dreams

Frozen Dreams bring Dead Reckoning to T.O.

October 09, 2018

OK, so the photo is from Back in the Day. August 1999, to be precise. That would be me on King William Island as taken by the late Louie Kamookak. We were atop Mount Matheson on King William Island. Behind me: Rae Strait.

I'll probably mention this adventure when I give an illustrated talk called FROZEN DREAMS: Dead Reckoning in the Northwest Passage. That's going to happen in the near future at three different venues in the Toronto area.

The talk is based on my 14th book, Dead Reckoning, which is now available in paperback. The book challenges the conventional history of Arctic exploration and highlights the contributions of fur-trade explorers and the indigenous peoples, notably the Inuit.

In recent times, I have been visiting the Arctic almost every year, sailing as a resource historian with Adventure Canada. I am also involved in planning the 2019 Arctic Return Expedition, which will retrace the 1854 journey of explorer John Rae, who discovered the final link in the first navigable Northwest Passage. Hope to see you here or there!

Oct. 30: Arts & Letters Club

Nov. 5: Canadian Federation of University Women, Mississauga

Nov. 14: Carlton Theatre Lecture Series

1960s

crime novel

detective novel

Haight-Ashbury

Sixties

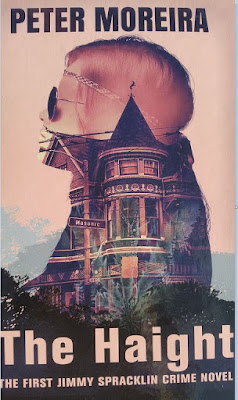

Detective hunts psychopathic killer in Sixties San Francisco

September 14, 2018

Hands up if you remember when the Haight-Ashbury was THE place to be. Well, it was a magical time, let me tell you -- before it went bad. Peter Moreira's detective novel, set shortly after the Summer of Love, finds detective Jimmy Spracklin trying to solve a series of brutal murders in The Haight. Spracklin is a terrific tough-guy detective. Of course he is flawed. His marriage is in trouble, partly because he is fiercely committed to his job. And he is desperate to find his teenage stepdaughter, who disappeared into the District some months before. Moreira sets his eventful crime novel against the larger political landscape, as Spracklin is also a Kennedy Democrat hoping that Senator Bobby Kennedy will give his career a boost. The author builds the stakes with every twist and turn, and when the daughter takes up with a psychopathic killer, Spracklin's quest becomes a race against time. Highly recommended for those who enjoy a cracking good detective story -- or for anyone who remembers when the Haight was the centre of the universe.

Arctic exploration

Canadian mysteries

Franklin expedition

polar bears

MYSTERY SOLVED!!! Polar Bears explain Fate Of the Franklin Expedition

September 07, 2018

Polar Bears Explain the Fate of the Franklin Expedition

What happened to the Franklin Expedition? Researchers have been debating that since 1847, two years after Sir John Franklin disappeared into the Arctic with 128 men. From the note later found at Victory Point on King William Island, most people believe that in April 1848, 105 men left the two ice-locked ships. The note tells us that already, nine officers and fifteen seamen had died. That represents 37 per cent of officers and 14 per cent of crew members. Historians have scratched their heads: why such disproportionate numbers?

Researchers have spent vast amounts of time and energy inquiring into the deaths of the first three sailors to die, whose graves remain on Beechey Island. Did lead poisoning kill them? Botulism? Zinc deficiency leading to tuberculosis? But wait. Maybe those three early deaths were anomalies – exceptions that tell us nothing about subsequent events. Perhaps the other twenty-one dead -- nine officers, twelve sailors -- died because of some event, some accident or injury.

A few scientists have wondered if these twenty-one men ingested something that others did not. But nobody, to my knowledge, has publicly invoked the calamitous Danish-Norwegian expedition of the early 1600s, which lost sixty-two men out of sixty-five. In 1619-20, while seeking the Northwest Passage, the explorer Jens Munk led two ships filled with sailors into wintering at present-day Churchill, Manitoba.

In my book Dead Reckoning, drawing on Munk’s journal, I detail the unprecedented miseries that ensued. During my research, I had turned up an article by Delbert Young published decades ago in the Beaver magazine (“Killer on the ‘Unicorn,’" Winter, 1973). It blamed the catastrophe on poorly cooked or raw polar-bear meat.

Soon after reaching Churchill in September 1619, Munk reported that at every high tide, white beluga whales entered the estuary of the river. His men caught one and dragged it ashore. Next day, a “large white bear” turned up to feed on the whale. Munk shot and killed it. His men relished the bear meat. Munk had ordered the cook “just to boil it slightly, and then to keep it in vinegar for a night.” But he had the meat for his own table roasted, and wrote that “it was of good taste and did not disagree with us.”

As Delbert Young observes, Churchill sits at the heart of polar bear country. Probably, after that first occasion, the sailors consumed more polar-bear meat and Munk did not think to mention it. During his long career, he had seen men die of scurvy and knew how to treat that disease. He noted that it attacked some of his sailors, loosening their teeth and bruising their skin. But when men began to die in great numbers, he was baffled. This went far beyond anything he had seen. His chief cook died early in January, and from then on “violent sickness . . . prevailed more and more.”

After a wide-ranging analysis, Young points to trichinosis as the probable killer —a parasitical disease, not fully understood until the twentieth century, which is endemic in polar bears. Infected meat, undercooked, deposits embryo larvae in a person’s stomach. These tiny parasites embed themselves in the intestines. They reproduce, enter the bloodstream and, within weeks, encyst themselves in muscle tissue throughout the body. They cause the terrible symptoms Munk describes and, left untreated, can culminate in death four to six weeks after ingestion.

So, back to the Franklin expedition. Could trichinosis, induced by eating raw polar-bear meat, have killed those nine officers and dozen seamen? And galvanized the remaining men into abandoning the ships? And rendered many of them so sick that they could hardly think straight or walk. And made some of them so horribly sick that they had to be quarantined into a separate tent?

In recent years, while visiting Beechey Island with Adventure Canada, more than once my fellow voyagers and I have been driven off by polar bears. We retreat into the zodiacs at first sign of approach. In that same situation, spotting a polar bear, how would Franklin’s men have responded? They would have killed those bears and eaten them -- perhaps bringing some of the meat onto the ships. That undercooked polar-bear meat, unevenly distributed among officers and crew, might well have led to the lopsided fatality statistics . . . and to all the rest. So, anyway, I suggest in Dead Reckoning.

When I put forward this theory to online-friends, some balked. By the time Franklin sailed, they observed, in the mid-19th century, Royal Navy officers knew that bear meat could wreak havoc in the human body, even if they did not fully understand exactly how. This is undoubtedly true. But then a supportive contributor drew attention to a contemporary video broadcast in which an expert hunter describes how he and his companions got horribly sick after eating poorly cooked bear meat. On an episode of Meat Eater, Steven Rinella admits to feeling mortified: “I have been preaching about the importance of cooking bear meat to my viewers and readers for a decade now,” he says, “and it’s really embarrassing.”

Rinelli knew very well that bear meat could be dangerous. But he went ahead and ate it anyway. Can anyone doubt that the men of the Franklin expedition, subsisting on short rations, desperate for a change of diet, would have made the same decision? Within the next few years, Parks Canada will almost certainly turn up some decisive evidence -- written records or human remains or both -- as divers investigate the Erebus and Terror. Until then, my money is on polar-bear-meat-induced trichinosis.

This essay turns up on a wonderful website devoted to Canadian mysteries. Check it out at The Franklin Mystery: Life and Death in the Arctic.

Arctic exploration

Dead Reckoning

indigenous peoples

inuit

native peoples

northwest passage

Lovely paperback edition lists under $20

August 30, 2018

The paperback is here! A single author's copy anyway, with countless others flowing into bookstores next week. Hats off to the folks at HarperCollins Canada! What a lovely package! This edition is slightly smaller than the hardcover . . . the perfect size!And it contains new and improved maps! And here on the back cover, a reviewer says, "This book is a masterpiece. . . . " And what is not to love about a list price under $20? OK, one cent under . . . but still! My day, no my week, is made.

The paperback is here! A single author's copy anyway, with countless others flowing into bookstores next week. Hats off to the folks at HarperCollins Canada! What a lovely package! This edition is slightly smaller than the hardcover . . . the perfect size!And it contains new and improved maps! And here on the back cover, a reviewer says, "This book is a masterpiece. . . . " And what is not to love about a list price under $20? OK, one cent under . . . but still! My day, no my week, is made.

adventure canada

Celtic Life International

Highland Clearances

Isle of Skye

Voyage around Scotland inspires Celtic Life spread on the Highland Clearances

August 28, 2018

The October issue of Celtic Life International features a gorgeous 3-page spread on the 1853 Highland Clearances at Knoydart. The writer -- that would be moi -- turned up in the vicinity by great good fortune while sailing with Adventure Canada earlier this year. A version of the article, which begins roughly as below, will turn up in a 2019 book to be published by Patrick Crean / HarperCollins Canada. Working title: SPIRIT OF THE HIGHLANDERS: How the Scottish Clearances / Created Canada's First Refugees.

The October issue of Celtic Life International features a gorgeous 3-page spread on the 1853 Highland Clearances at Knoydart. The writer -- that would be moi -- turned up in the vicinity by great good fortune while sailing with Adventure Canada earlier this year. A version of the article, which begins roughly as below, will turn up in a 2019 book to be published by Patrick Crean / HarperCollins Canada. Working title: SPIRIT OF THE HIGHLANDERS: How the Scottish Clearances / Created Canada's First Refugees.

On day four out of the resort town of Oban, we awoke to

find our expeditionary ship anchored in Isleornsay harbour off the Isle of

Skye. This was not a planned stop. Overnight, faced with southwesterly winds

gusting to 60 and 65 knots, the captain had taken the Ocean Endeavour north into the Sound of Sleat that runs between

Skye and the mainland. Here he had found shelter in one of the most protected

harbours on the east coast of Skye.

June 2018. We were circumnavigating

Scotland, my wife, Sheena, and I, with Adventure Canada. We had stopped in

Islay and would soon visit Iona, St. Kilda, Lewis, Shetland, Orkney. We were among roughly 200 passengers and I

was one of several resource people available to hold forth on matters of

historical interest. This surprise anchorage

drove me to my maps.

For the past few years, I had been researching

Scottish Highlanders who emigrated to Canada in the 18th and 19th

centuries. Some made the move of their own volition, but most were refugee

victims of the Highland Clearances. During one of those Clearances, I recalled,

a ship called the Sillery had anchored

here at Isleornsay harbour. It had arrived late in July 1853 to carry off farmers

who lived along the north shore of Loch Hourn, a broad inlet that enters the

mainland six or eight kilometres due east of Isleornsay. That area was part of

Knoydart in Glengarry.

I remembered wondering why the Sillery had not entered that inlet to reduce transport time. Now, onboard

experts suggested that strong westerly winds – not unusual in these parts –

would have made it difficult for any 19th-century sailing vessel to

emerge out of that inlet. That explained why the Sillery had anchored in this sheltered harbour and the captain had set

his crewmen to rowing across the sound.

Almost 100 years before that, in 1746, farmers from Knoydart

had been among the 600 Highlanders who followed Macdonell of Glengarry into the

catastrophe known as the Battle of Culloden. In the decades that followed, some

had emigrated to Upper Canada and others to Nova Scotia. Still, by 1847, more

than 600 people remained in the coastal settlements, though their numbers were then

reduced by the Great Famine. But activist-journalist Donald Ross, who collected

first-hand accounts of several Clearances, wrote that these crofters needed

only a little encouragement to resume thriving as farmers.

In 1852, however, the newly widowed Josephine Macdonell

gained control of the Knoydart estate. A Lowland industrialist named James

Baird – a Tory member of Parliament -- had expressed interest in acquiring her

lands, but only if they were unencumbered by paupers for whom he would become legally

responsible. Ignoring the people’s offers to pay arrears caused by the potato famine,

the widow Macdonell issued warnings of removal. “Those who imagine they will be

allowed to remain after this,” she wrote, “are indulging in a vain hope as the

most strident measures will be taken to effect their removal.”

In April 1853, she informed her tenants that they would be

going to Australia, sailing courtesy of the landlord-sponsored Highland and

Islands Emigration Society.

In June, she amended that: they would travel instead to Canada, their passage

paid as far as Montreal. On debarkation, they would each be given ten pounds of

oatmeal. After that, they were on their own.

On August 2, 1853, with the Sillery anchored at Isleornsay, men with axes, crowbars, and

hammers rowed across the inlet and landed. They joined a gang of mainlanders and

began clearing farmers from their homes. The factor in charge ordered that after removing the tenants, his men were immediately to

destroy “not only the houses of those who had left,” Donald Ross wrote, “but

also of those who had refused to go.”

Burly men ripped off thatched roofs, slammed picks into

walls and foundations, and chopped down any supporting trees or timbers.

Eventually, Ross wrote, “roof, rafters, and walls fell with a crash. Clouds of

dust rose to the skies, while men, women and children stood at a distance,

completely dismayed.” According to Ross, "The wail of the poor women and

children as they were torn away from their homes would have melted a heart of

stone."

(To read the rest, check out the October issue of Celtic Life International.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Before turning mainly to books about arctic exploration and Canadian history, Ken McGoogan worked for two decades as a journalist at major dailies in Toronto, Calgary, and Montreal. He teaches creative nonfiction writing through the University of Toronto and in the MFA program at King’s College in Halifax. Ken served as chair of the Public Lending Right Commission, has written recently for Canada’s History, Canadian Geographic, and Maclean’s, and sails with Adventure Canada as a resource historian. Based in Toronto, he has given talks and presentations across Canada, from Dawson City to Dartmouth, and in places as different as Edinburgh, Melbourne, and Hobart.